Legend has it that Three Rivers, the rural city where I live, used to be a gathering place for sacred ceremonies for the indigenous tribes who lived in the region before white settlers came in and laid claim. I haven’t been able to track down any proof of this assumption, but it’s one of the things we tell ourselves to explain why there’s a Benedictine monastery, a Mennonite retreat center, an interfaith retreat center, and several other contemplative and cultural communities who now call this place home.

This history might also help explain what I’ve come to see as a pattern of contested byways. I don’t think this type of pattern is unique to Three Rivers, as populations and modes of transportation have proliferated everywhere on this planet, but I can only begin to understand it through the unique ways it manifests itself in my community, both literally on the ground and figuratively in the stories we tell, the policies we set, the identities to which we cling.

Take hedgerows, for example. Anyone who’s carpooled with me in the winter in our rural area knows that I can get on a soapbox about hedgerows, and the most recent late-winter snowstorm resurrected the issue for me. Most of our city had a snow day, but as part of the crew responsible for snow removal at the retreat center where we work, my friend David and I had to brave the roads. By the time we had taken care of business and headed back into town together, the sun had melted most of the accumulation and the county plows had been through several times. And then we hit that spot on Hoffman Road where the fields had been clear cut to make way for row crops and irrigation: snow was blowing perpendicular to the road so hard and fast that I couldn’t see the lanes or any vehicles coming from the opposite direction. We made it home safely, but over the course of the next day, I noticed that friends’ social media feeds had filled up with pictures of accidents and reports of other dangerously drifted roads throughout the county.

This particular storm finally blew me over the edge and I started doing my homework to discover some of the background on this situation and write a letter to the county road commission. One of my concerns is that, by clearing hedgerows and planting every possible square inch of land, large-scale farms are externalizing the costs of their own profits to the county taxpayers in terms of both increased road clearing costs and decreased safety. In addition, as our agricultural ancestors knew, hedgerows are good for our ecology: they prevent topsoil erosion, which is becoming an increasingly critical food security issue, and they provide habitat and corridors for the wildlife that help control pests, eat our leftovers, pollinate our plants, and fertilize our soil. If the free market isn’t going to incentivize these essential, common sense practices, I argue in my letter, it’s up to our civic leaders to find ways to uphold them for the common good.

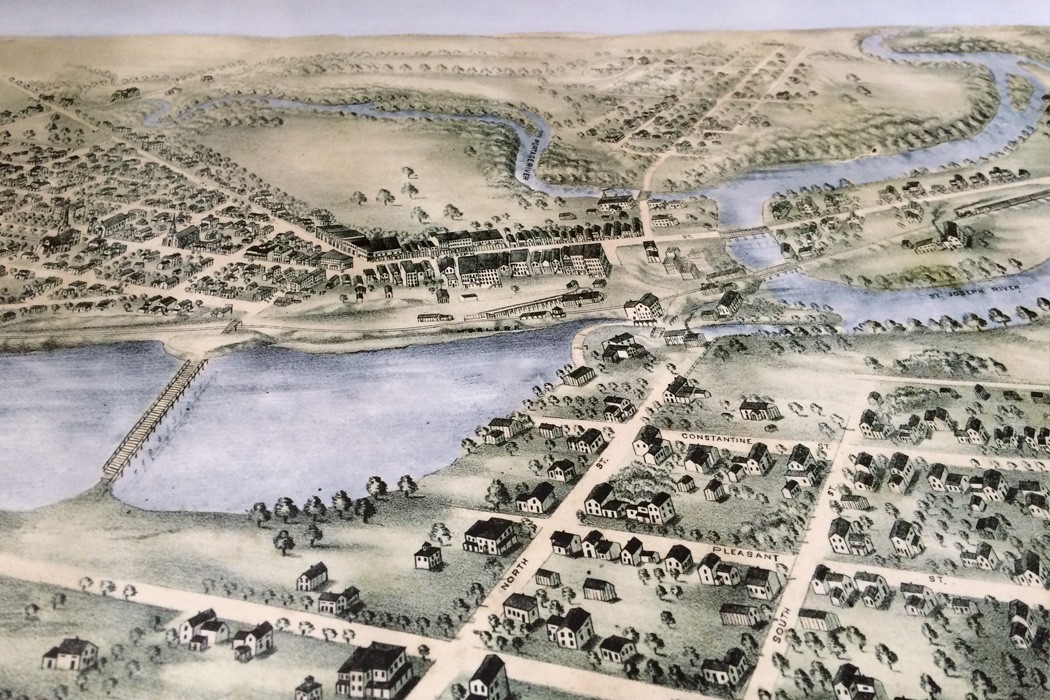

And yet I recognize that I’m advocating for policy and practices on land that isn’t mine—that was, in fact, stolen. Long before big ag stripped our oak savannah prairie for perennial cash crops and long before Enbridge plowed their way through our community for yet another crude oil pipeline threatening holdouts with property condemnation, settlers of European descent rode the wave of westward expansion as it crashed over the convergence of three small rivers in southwest Michigan. Looking out the back window of my apartment toward a bend in the Portage River, I imagine the parking lot between here and there as a giant asphalt headstone—an unmarked, sacrilegious memorial to the ghosts of all those who walked here freely before we buried them and their stories under the unholy geometry of our platte maps. It is guarded on either side by two pairs of Dumpsters™, whose real names we have also mostly forgotten outside of the convenience of corporate branding. Taking the long view, writing a letter to the road commission about hedgerows feels a bit like trying to stay dry in a downpour under a cocktail umbrella.

But I’ll do it anyway because first steps are always halting and ridiculous, especially when we’re trying to head in the direction of repentance. I think of the deer with the broken leg who lives in a stand of sumac where I work and knows too much of contested byways not in her head, but in her bones. She’s learning to come when we call and every time we feed her, it’s an apology for what we humans have done with our guns and our cars, and the collective mythology that allows us to think we can every truly own the road.