I’m debating whether I can summon the energy to get out of bed between snippets of NPR on the clock radio. Through my bedroom windows, I hear the soft sighs of drivers going by on their way to work at downtown district speeds and the aluminum clacking of ladders that marks the beginning of another day of restoration on our neighbor’s historic storefront. The three-story, brick wall faces west, a thermal mass oven in the afternoons as the painters sweat out the tension between perfection and a deadline. I’m nervous for the young woman who doesn’t appear to wear sunscreen. On my nightstand is the novel I’m currently reading, Island Beneath the Sea by Chilean-American author Isabel Allende. It follows the story of a woman named Tété who was born into slavery in San Domingue, which later became the independent country of Haiti after a slave revolt in the early nineteenth century. Her fictional life floats in and out of the factual narrative, in which slave owners debate whether it’s more profitable in the long run to work and discipline slaves to an early death and then buy new ones, or to spare the rod on your human capital. Rape, decapitation, hanging, crushing labor, broken spirits: I live and work every day in a country that was founded on top of the worst we human beings can do to each other. The alarm goes off again. Italy has rescued 6,500 people from boats off the coast of Libya, and Donald Trump is still talking about building a wall at the Mexico border.

Lord, have mercy.

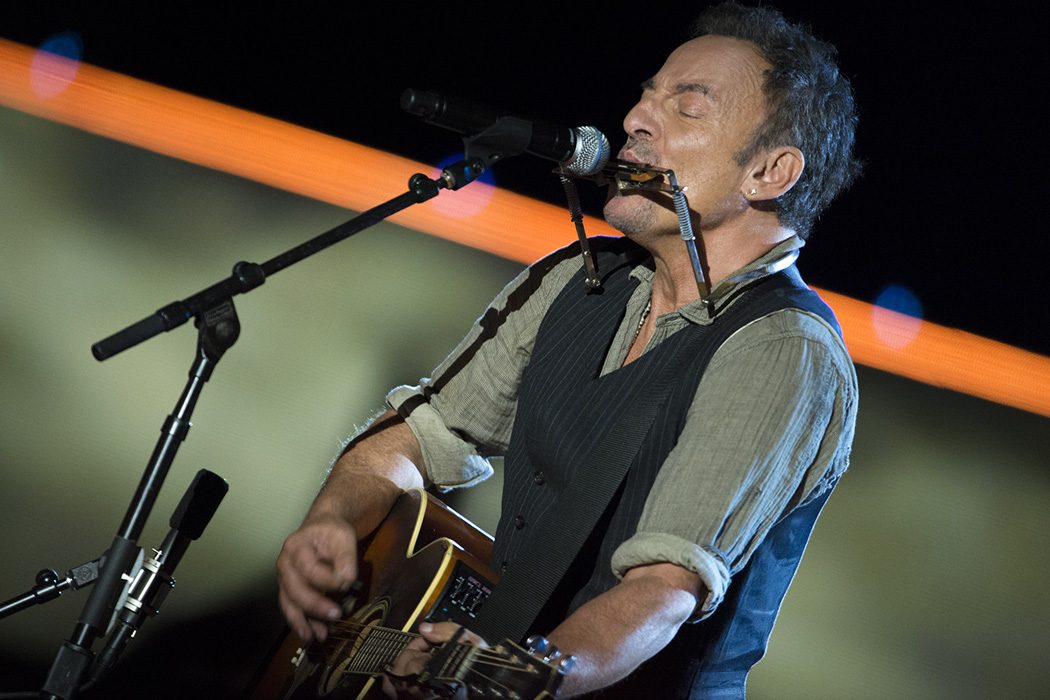

I’m at a Bruce Springsteen concert in the very last row of a mostly white, middle-aged crowd. Some were lured by the nostalgia of his early work, the soundtrack for their teen years—first loves, first cars, drinking cheap beer out of cans, life as an open question with infinite answers. Some resonate on a deeply personal level with his working class themes, which come out in songs like “Jack of All Trades,” written in response to the Great Recessions’ disproportionate effect on the average worker:

I’ll hammer the nails, and I’ll set the stone.

I’ll harvest your crops when they’re ripe and grown.

I’ll pull that engine apart and patch her up ’til she’s running right.

I’m a Jack of all trades, we’ll be alright.

A hurricane blows, brings a hard rain.

When the blue sky breaks, feels like the world’s gonna change.

We’ll start caring for each other like Jesus said that we might.

I’m a Jack of all trades, we’ll be alright.

With uncontained joy at the first distinctive chords, the woman next to me chants, “Hungry heart, hungry heart,” and then proceeds to sing her favorite song along with the Boss, loudly and off-key. I think of Renee, a neighbor I met this summer. She’s raising five young boys, the sons of mostly absent fathers, and also has a niece in her care whose mom is currently living in her car. Renee works at one of the local factories and her body is breaking down. She goes to a chiropractor three times a week for chronic pain, and can’t advance her position at work because of her physical limitations. I’m guessing it’s only a matter of time before she won’t be able to perform her current job. Too many of our neighbors here in Three Rivers work full-time and yet live in perpetual financial insecurity. “The banker man grows fatter, the working man grows thin. / It’s all happened before and it’ll happen again. / It’ll happen again, they’ll bet your life. / I’m a Jack of all trades and, darling, we’ll be alright.” The Boss knows what’s up.

Christ, have mercy.

As the sun lowers in the west, I’m out on the Huss Project Farm, where we grow vegetables to sell at the farmers market and distribute to neighbors in need. I harvest beets and I also pull weeds as I go, laying them down between beds to mulch the footpath. July’s drought followed by multiple deluges in August has fostered a forest of weeds, and I think of my friend Elisabeth’s poem, written for the inaugural issue of Topology: “A pause for hearing the sound weeds make / when you pull them up, their roots softly snapping / down in the damp earth, a low orchestra tuning / its strings past the breaking point.” Across the street, our Spanish-speaking neighbors are relaxing in the backyard shade, with Beyoncé pumping through the speakers: “Middle fingers up, put them hands high. / Wave it in his face. Tell him, “Boy, bye.” / Tell him, “Boy, bye. Boy, bye.” Middle fingers up, / I ain’t thinkin’ ‘bout you.” Our neighborhood is a seasonal home for many migrant workers with whom I, knowing only the language of privilege, can’t communicate. I swat at the swarm of mosquitoes borne of recent rains and know I can go home whenever I feel like it.

Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us.

I visit St. Gregory’s Abbey as often as I can, and less often than I’d like, for prayer services. Living a life ordered by the Rule of St. Benedict, the community anchors my longing for contemplation, even as I drift far and wide in a sea of action. Ora et labora—“pray and work”—is the most simple version of that rule as I understand it, which has been my life raft even outside the boundaries of the monastery. Inside the church, we form a circle around the altar to receive the body and blood of Christ, and during the Eucharistic liturgy with my head bowed, I can never avoid getting lost in the patterns of the huge, gorgeous wool rug that lies between our feet and the slate floor. With intricate patterns that are at once organic and geometric, the rug has become a sensory trigger for me, bringing me back to the taste of bread and wine like a Springsteen song might bring someone back to the party on that fateful night. I’ve come to appreciate that rug not as a distraction, but as an object that saves me from whatever personal piety such a practice might engender. The world is here with me, as I think of the weavers and the generations of craft that went into the intricate, intense work of creating such a massive work of art. And if I let my imagination wander further as I pass the peace and take the cup, I also think of migrant workers and painters, of rock stars and R&B stars, of farmers and radio announcers. I think of Renee, and all those whose bodies are scarred by generations of injustice. I think of everyone whose labor upholds my life each day, many of whom also, undoubtedly, pray. The monks hold them all in constant prayer, and I long for the day that we all hold each other as dearly in thought and deed, in personal relationships and in systems, like Jesus said that we might.

Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.