Editor’s note: A portion of this essay was originally published in Geez Magazine, issue 34. Photos from “Conquest of the Land Through Seven Thousand Years,” W.C. Lowdermilk. Assistant Chief, US Dept. of Agriculture. Soil Conservation Service. Feb. 1948.

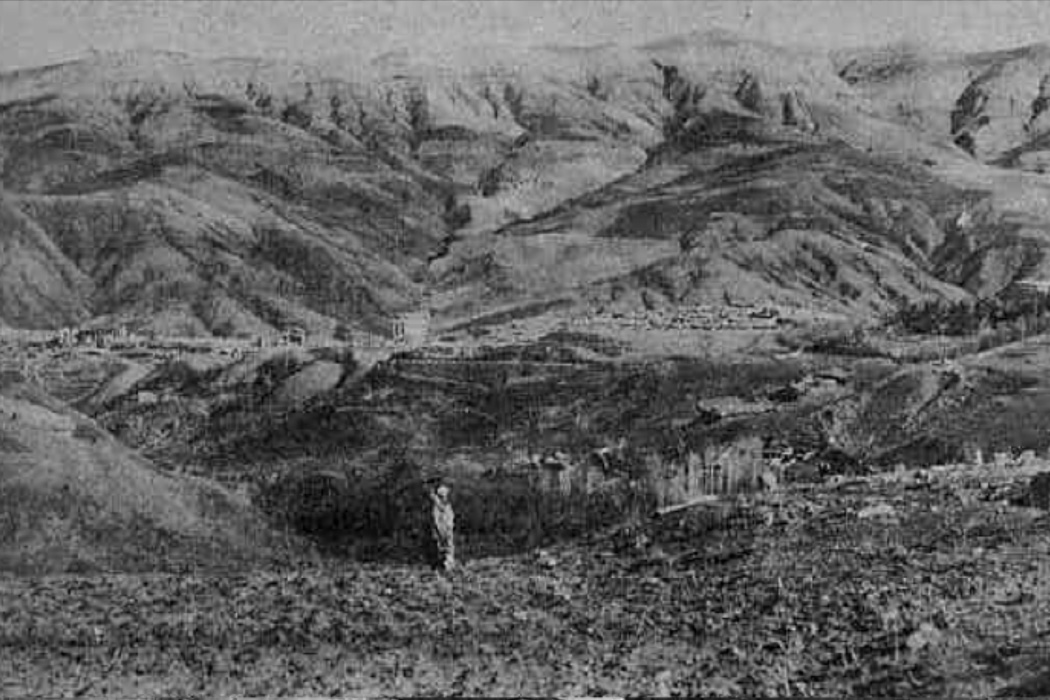

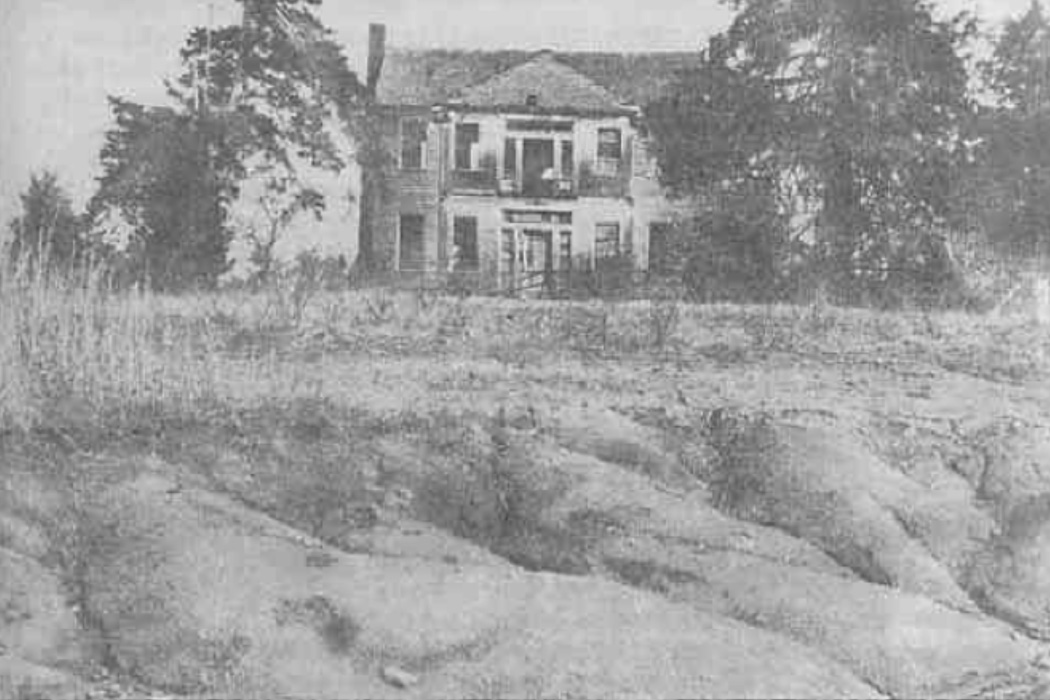

In 1948 the American soil scientist W.C. Lowdermilk published a paper titled “Conquest of the Land Through Seven Thousand Years.” The paper was a report on Lowdermilk’s travels in Europe and the Middle East to study the long-term impact of soil degradation on the landscape. His findings provided the foundation for soil conservation education in the United States for years to come, and clearly documented the fact that the “conquest of the land” is a self-defeating enterprise.The most striking feature of Lowdermilk’s report are the photographs in which he dramatically connects the failure of a civilization to nurture the health of its soil with the failure of civilization as a whole. Ancient Roman ruins in North Africa are frequently presented in the context of the gullied hillsides and sparse deserts in what was once the breadbasket of the Roman Empire, providing the bulk of the agricultural produce that fed the empire at its peak while supporting cities like Cuicul, Timgad, and Carthage. Overgrazing and cultivation of the hillsides, expressions of political will administered from a far-distant capitol, ruined this once productive landscape so completely that it has not begun to recover in the 17 centuries since. Lowdermilk invites us to observe, in the caption to the photo of Cuicul, that the ruin of the land “is almost as complete as the ruin of the city.” Amid the ruins of Timgad we can make out the “squalid huts” of the approximately 300 inhabitants, “which is all that the eroded land will support at present.”

If we could photograph the mental environment of the Roman Empire and see the impact of the imperial imagination on the minds of its citizens with the same clarity as we can see the physical impact on the environment, what would that look like? Would we see imaginations strip-mined of any sense of themselves as anything other than citizens of the great abstraction that is empire? The fertile soil of individual identity in the personal context of their home place and time washed away in the cultivation of political necessity? What stories were the citizens of Cuicul telling to one another as their once healthy land degraded steadily year by year?

Stories can serve to locate us in our own particular time and place. They can tell us, as Northrop Frye put it, “where is here.” But, like any aspect of culture, they can also be used towards the opposite end. Language can obscure, repress, dislocate, and exploit human lives and communities. In all cases the central issue is the ability of people to imagine our world into being, for better or for worse, and to imagine ourselves as part of any number of smaller or larger communities. If we lose faith in our ability to imagine, and thereby shape, our reality we fall into despair.

One thing is sure. The earth is now more cultivated and developed than ever before. There is more farming with pure force, swamps are drying up, and cities are springing up on unprecedented scale. We’ve become a burden to our planet. Resources are becoming scarce, and soon nature will no longer be able to satisfy our needs.

– Tertullian, Roman theologian, 200 AD

Jamaica Kincaid provides a powerful description of the literal “uprootedness” of the colonial experience. She explores the connections between power, place, and language in a chapter titled “To Name is to Possess” in her My Garden (Book), providing a detailed discussion of the ways in which power asserts itself through dislocation and language, even in the case of something as apparently innocuous as a botanical garden.

I do not know the names of the plants in the place I am from (Antigua)… I was of the conquered class and living in a conquered place; a principle of this condition is that nothing about you is of any interest unless the conqueror deems it so. For instance, there was a botanical garden not far from where I lived , and in it were plants from various parts of the then British Empire, places that had the same climate as my own; but as I remember, none of the plants were native to Antigua… The botanical garden reinforced for me how powerful were the people who had conquered me; they could bring to me the botany of the world they owned.

Barry Lopez, by contrast, explains how people who value a personal, lived relationship with their home place act as a counter to the distortions of a national geography intended to shape a national, consuming public. He writes of his growing awareness of the rich resources available to anyone with a genuine desire to step outside of their assumptions about geography, and really discover what the soil and story of a particular place have to teach. He affirms the corporeal specificity of each person’s interaction with place as an essential step towards the healing of our culture, and perhaps the development of our ability to re-imagine our communal discourse as something other than a force of personal, physical, and cultural destruction:

It is through the power of observation, the gifts of eye and ear, of tongue and nose and finger, that a place first rises up in our mind; afterward it is memory that carries the place; that allows it to grow in depth and complexity. For as long as our records go back, we have held these two things dear, landscape and memory. Each infuses us with a different kind of life. The one feeds us, figuratively and literally. The other protects us from lies and tyranny.

When I worked in theatre I was at times struck by the way in which a particularly good performance could make the world more “real.” I vividly recall walking home one winter evening after a performance of Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, when my senses seemed particularly heightened. The sharpness of the cold air, the sound of the snow crunching beneath my feet, the brightness of the city under the streetlights…the entire world seemed alive with possibility because of the intensity of the imaginative experience the company had shared with its audience that evening.

In my work now as a farmer, I find that healthy soil provides a similar excitement. The tilth of good soil squeezed in the fist seems to pulse with possibility. It invites a response, much like a compelling story or work of art: a new way of imagining what the world can be. The words “culture” and “cultivate” are rooted in the Latin word cultus, which meant simultaneously “to inhabit, to till, and to worship.” An actor and audience physically and imaginatively sharing the same space; a farmer harvesting a bushel of potatoes from soil she has carefully tended; both are embodying traditions that go back to the earliest glimmerings of culture and are at the heart of what it means to be human.