Christ climbed down

from His bare Tree

this year

and ran away to where

there were no rootless Christmas trees

hung with candycanes and breakable stars…

from “Christ Climbed Down,” Lawrence Ferlinghetti

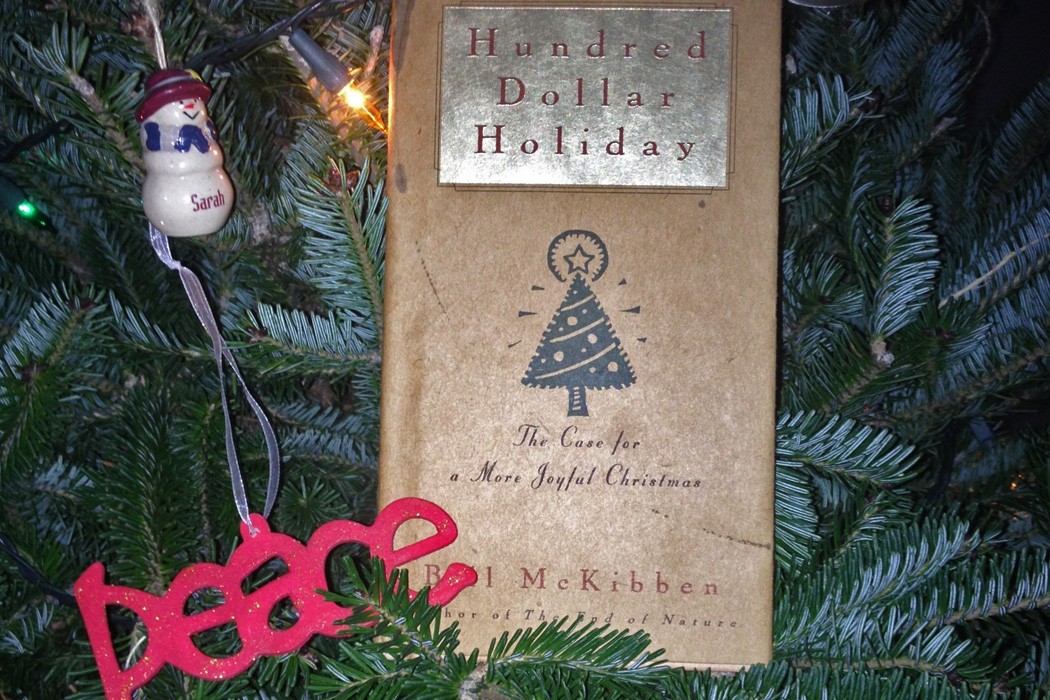

Bill McKibben wrote his book, Hundred Dollar Holiday: The Case for a More Joyful Christmas, out of a growing awareness that the celebration of Christmas in the late twentieth century “had become something to endure at least as much as it had become something to enjoy.” As he and members of his rural New England church community began to explore the possibilities of a simpler approach to celebrating the season, they realized that the consumer feeding frenzy, rounds of obligatory parties, and related excess which have come to characterize the season for many people were actually cheating them of the one thing they wanted most from a Christmas celebration: joy.

The Hundred Dollar Holiday campaign began as a conversation about what a simpler, more joyful holiday celebration might look like. A hundred dollar cap on spending was less about de-materializing the holiday, than it was about spurring a thoughtful and creative attitude about what kinds of shared activities and events actually brought the people involved the most joy.

Early in the book McKibben takes his readers on a quick tour of the history of Christmas, from the third-century Roman Christians replacing the feast of the invincible sun-god Mithras, celebrated on December 25 (winter solstice in the old Julian calendar), with that of their infant savior; to Clement Clarke Moore’s invention of the Santa Claus tradition in his poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” in the early nineteenth century; to big department store owners in the 1920s and 1930s incorporating Santa Claus into their Thanksgiving Day parades and convincing “FDR to move Thanksgiving back a week to insure a month-long window for undistracted shopping.”

He notes that the development of the particularly American approach to Christmas throughout the nineteenth century, as documented by the Christmas historian Stephen Nissenbaum, “served as a way to educate Americans, traditionally distrustful of luxury and excess, to the joys of buying things they didn’t strictly need”:

It was the thin end of the wedge by which many Americans became enmeshed in the more self-indulgent aspects of consumer-spending…a crucial means of legitimizing the penetration of consumerist behavior into American society.

McKibben acknowledges that an emphasis on gifts and a more material form of celebration made some sense in previous centuries when the majority of Americans lived either on farms or in city slums and their lives consisted largely of unremitting hard work. He cites the example of reading Laura Ingalls Wilder with his daughter, in which a couple of pieces of stick candy and a rag doll become a genuine source of delight, and reflects that “when you have a lot of stuff, getting more of it is less exciting than when you have very little.”

We eat rich food year-round; there’s always freshly fermented beer; we don’t need to beg the lord of the manor for a glass of wine. In fact, what’s happened is that most of us have managed to become lords of the manor, living relatively easy and abundant lives. We have sumptuous clothes and lots to eat. Since we live with relative abandon year-round, it’s no wonder that the abandon of Christmas doesn’t excite us as much as it did a medieval serf. We are—in nearly every sense of the word—stuffed. Saturated. Trying to cram in a little more on December 25 seems kind of pointless.

McKibben has two main points he wants us to take away from this short book. The first is that there is nothing particularly sacrosanct about the forms and traditions of our Christmas celebrations. Almost everything we associate with the holiday has a specific time and place of origin that we can point to, and was taken up because it addressed a specific cultural need or desire at the time. McKibben invites us to consider who we are now, and evaluate whether the forms and traditions we have inherited still carry meaning for us, whether they bring us joy.

The second is that Christmas should be a reflection of what we value most, and we should make that the center of our celebration. He and members of his community decided that in a time of material excess, material excess was not what they wanted to celebrate. Taking time to be with one another in a busy life; finding stillness in a world of constant noise and distraction; finding gifts for loved ones that could not be found in a store; these are the activities that can serve to reawaken an experience of joy in the Christmas season. This is the real counter-cultural celebration that can inspire an image of, as Lawrence Ferlinghetti put it, “the very craziest of Second Comings.”