If it hadn’t been for a dog that refused to sleep in the house, I might have never given the stars a second glance.

As a true country dog, she believed her proper place was in a barn stall with straw on the floor. To doze indoors in 68-degree comfort on the living room carpet was not for her. Even on -20 degree nights, she’d bark, whine, scratch, and otherwise irritate until we (specifically, me) relented. I’d arise with a groan from the comfort of book and chair and we’d make the 5o-yard trudge in darkness to her nightly quarters.

Yet what began as a begrudging chore gradually grew into an agreeable ritual. There was something mildly satisfactory about it. I’d empty a cup of dry food into her bowl, and as the barn door thumped shut, it marked the decisive end of another day.

Once outside, I’d pause for the barn prayers: one Pater Noster and five Ave Marias. I’d first done so during a time of sickness and trial and this ritual, too, had stayed with me. I’d face north and Polaris would give its benediction while the dog contentedly crunched her ration.

It was on one of those clear winter nights that I first started to look in earnest at the stars. What struck me was their deep and remote silence; the only wilderness left still untouched by human hands or desire. While the stars hung beyond reach, they also seemed knowable, even companionable. Provided of course that I knew them, which inexcusably I did not. I’d been too absorbed by the ant-farm busyness of my puny earthly existence to pay their vast majesty the homage they deserved.

Suddenly, this seemed a shameful neglect. All I knew for sure were the Big Dipper and Orion, and to find those two was the mental equivalent of playing “Chopsticks.”

Moreover, our species in general has lately fallen into celestial ignorance. Twenty centuries ago, an unlettered Bedouin shepherd would’ve known more about the stars than most people do today, save for astronomers. The blandishments of central heat, electric lights, and various electronic distractions have lured us away from the great wheel of the heavens. We no longer tell myths about the stars or search their depths for signs of ancient prophecies fulfilled.

So that December evening, I resolved to take what the world would consider a giant step backwards. I would learn by sight and name the major constellations in the winter sky.

At first, I tried the obvious twenty-first century shortcut: a telescope. I’d gotten a discount store model two years earlier and had never seriously used it. Now that I did, it proved a major disappointment. By design, I found that a telescope focuses narrowly on a singular point in space. That’s no help at all if you want to find an entire constellation, and its position relative to those nearby.

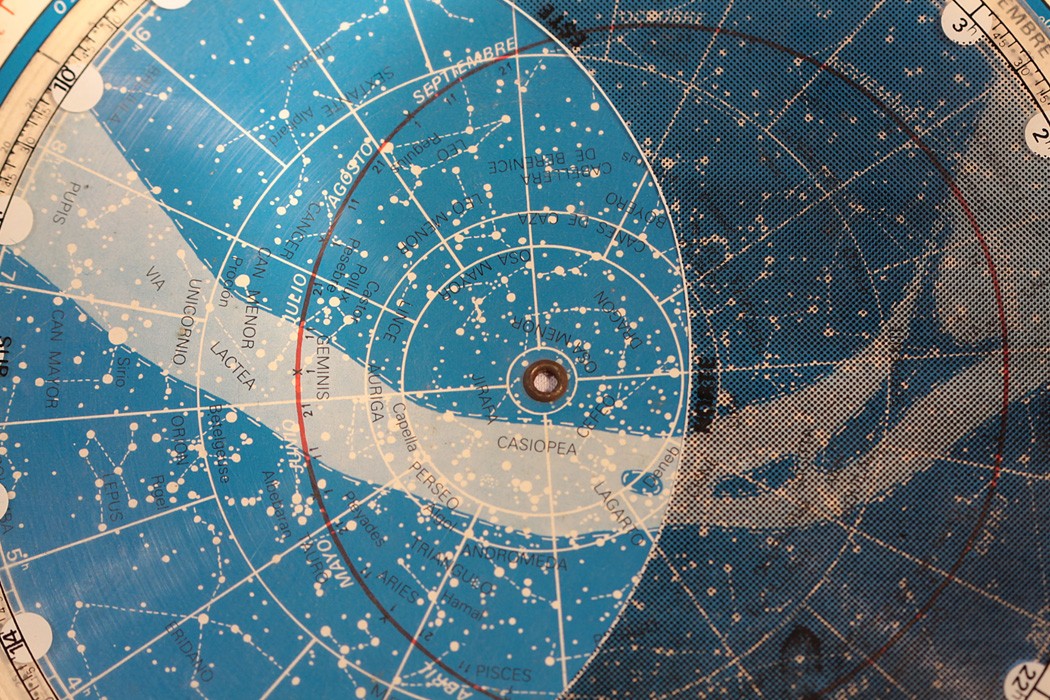

Instead, a $10 plastic star chart unlocked the secrets of the visible universe. My wife gave it to me for Christmas and it was perfect. It was made of two movable disks that could track a constellation’s location down to the very day and hour.

After supper, I’d swaddle myself in ice-fishing clothes and head to the field behind the barn. We have no yard light, so it was always darkest there. With a tiny red penlight to read the chart, I’d scan the vast canyons of space for patterns in the sky.

I was unaccompanied, but never alone. About 9:00 p.m., a band of coyotes would howl and yammer away from deep in the marsh. A bit later, the tremolo of a screech owl would echo from the little woods across the road. In the way of all natural sounds, these added to rather than subtracted from the winter quietude.

Then after several weeks, I realized something curious that my chart didn’t tell me: you can’t hear the stars, but you must nonetheless listen closely to see them.

Such listening isn’t done with the ears, but through attenuation of the body and spirit. While the time required to reach this state may vary, there does seem to be a common baseline. It takes about 20 minutes for the eyes to adapt to darkness; about 20 minutes for the body’s relaxation response to lower breathing rate, stress hormones, and blood pressure; and, once my feet get cold, about 20 minutes of aerobic walking down a starlit road to reap the calming benefits of exercise.

Not until I stilled myself would the stars—rather like black and white photos in a dark-room developer’s bath—gradually reveal themselves. Once the pupils dilate and mental focus sharpens, the naked eye does the rest. It wants to detect motion and patterns, even in the periphery. It’s eager to notice not just stars, planets, and airplanes, but the pinprick flash of satellites in high orbit. With each new object found, our latent ability to see the whole picture grows stronger.

For a non-scientist, the stars can be as much about legends writ large in the sky as they are astronomy. While new discoveries of galactic bodies bear sterile names such as M-42, the big constellations still tell a human story. Consider the Big Dipper: in the 1840s, northbound runaway slaves would “follow the drinking gourd” to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Centuries earlier, the Iroquois and Micmac Indians saw the Big Dipper as the tail of the Great Bear (Ursa Major). Which it still is. With the naked eye, you can readily see the stars that form his legs and feet. And imagine how the wounded bear’s blood would color the forests of North America with scarlet each autumn.

A broader vision also enriched my knowledge of Orion the Hunter. Previously, it had been a ubiquitous Touchdown Jesus figure who straddled the southern sky (per the giant tile mosaic of Christ that’s visible from the football stadium at Notre Dame.) After closer study, I could see the full tale. Yes, Orion’s a hunter, with the dog stars Sirius and Procyon running at his feet. Yet bounding further south was my favorite constellation, Lepus the Hare. One cannot and must not miss Lepus: it wears the only pair of bunny ears in the galaxy.

Similar revelations, too trifling to recount here, accompanied sightings of Auriga, Cassiopeia, Cephas, Leo, the Triangulum, the Pleiades, Bootes, Hercules, and so on. Within a few months, my affinity with these eternally distant blobs of gas and stardust felt personal. After they’d been obscured by bad weather, it brought great joy to find them above once more. They were so bright and boundless, so true in their silent fidelity. The booming theophany of Psalm 19 could’ve been written for winter nights such as these: “The heavens declare the glory of God, the skies proclaim the work of his hands …”

By the time the rains and fog of March came, I could identify 25 constellations. In practical terms, this meant I’d come to know just a few dozen of the 2,500 stars visible to an unaided eye. A pittance by astronomer’s standards, but not a bad haul for an amateur, I told myself.

However, the last lesson in my stargazer’s novitiate was perhaps the most profound. That’s when I learned what the stars have to teach us about trees.

It was a dark evening, but with snow on the ground in the country, there was plenty of ambient light. As was my habit, I studied the roadside trees as I walked. Bare of leaves, their limbs, trunks, and branches stood in stark relief against the sky. I stopped beneath my favorite tree, whose creamy crown had suffered a disastrous, if artful wound from a windstorm. The center of its wide crown had broken off like an enormous tooth. What remained where two massive, upright limbs. Some would see them as football goal posts (Touchdown Sycamore?). For me, the limb’s knobby elbows—surprisingly human—brought to mind Moses from the book of Exodus. It was his upheld arms, such as these, that gave the Israelites victory in battle over the Amelekites.

Although on this night, from my angle, it looked as if Sirius itself was perched in the sycamore’s broken crown. The two seemed in some inscrutable way connected. It was if the tree had cradled a natal star in its woody bosom. Which seems a silly implausibility until I realized the larger truth.

In fact, our brightest star, the sun, had made this tree and all trees the shape they have become. The extended finger of every twig; the cantilever reach of every branch; not a centimeter is unreasoned and unplanned. Each has turned itself in conscious response to a sun above that gives them life. So, too, the divine light that’s shaped my inner being, with its hopes, yearnings, and self-willed distortions.

Trees, stars, and souls—who knew they were of one piece? In their sudden likeness, it was good to see that each in its own way could point us home.