We sight the mornings softly

Take to them easy

The scent of the wood and coffee

Our cup is filling

Outside the river flows

Its course unfolding

A strength it never knows

A sweet outpouring

Joan Shelley, “Over and Even”

Last fall, a group of us from Topology led a workshop at the Earlham Writers’ Colloquium on writing from your watershed. After exploring what a watershed is and why it matters for us as writers and humans, we shared some prose and poetry excerpts from a variety of writers that exemplify watershed writing in some way. Then, we asked participants to spend 10 or so minutes writing about the body of water nearest to their home, either where they currently live, or somewhere they had lived in the past. As I took a mental tour of the places I grew up, I was surprised at what rose to the top of my mind.

In my early years, I was an amphibian girl. Anywhere there might be frogs or turtles was a place I wanted to be. I spent many early summers on Pleasant Lake in Three Rivers, Michigan, trotting up and down the shore with a net and eventually motoring around the whole lake hoping to catch something I could touch and examine and talk to and sometimes take home as a pet. It was because of my grandparents’ cottage on Pleasant Lake and the imaginative connection to a place that it engendered that I ended up in Three Rivers as an adult. I still pause whenever I walk a bridge over one of the rivers to see if I can catch a glimpse of anything—a little map turtle swimming stationary against the current or even a cluster of carp bottom-feeding around the pylon. Though Pleasant Lake has probably been the most formative waterway in my life, it wasn’t the one that came immediately to mind at Earlham that day, but one closer to my childhood home.

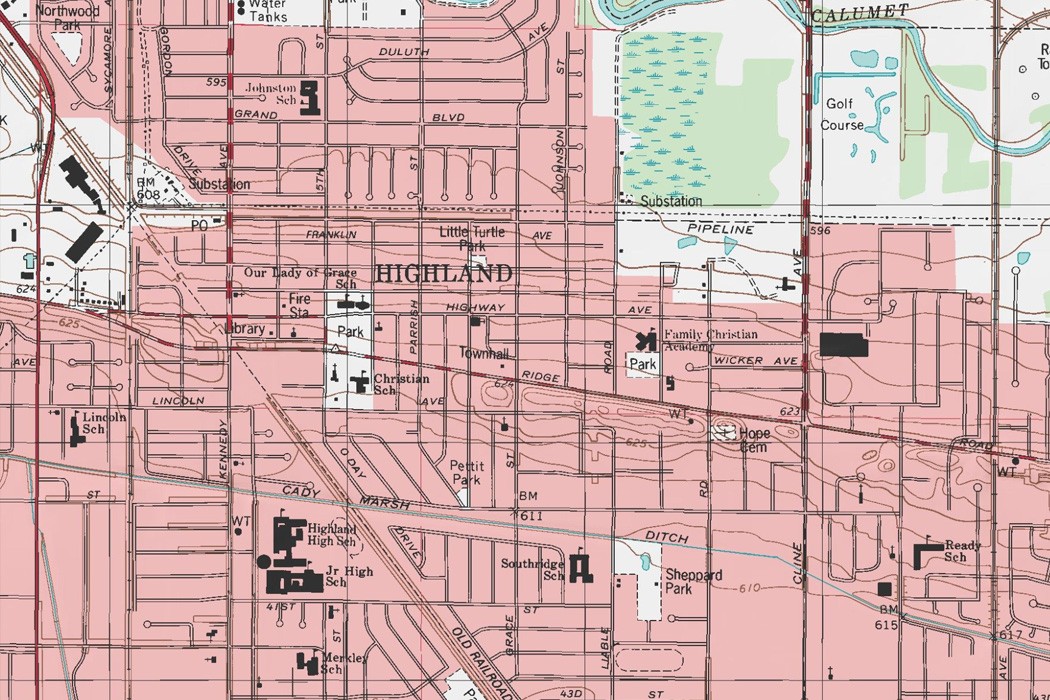

I don’t know how many years it had been since I had thought about Cady Ditch. As a kid, I had no concept of where the ditch came from, where it went, or what it was for. I just knew that my friend Marcy’s yard backed right up to the ditch and I was jealous. By the time I was old enough to bike to her house by myself, Marcy and I were growing apart, but I have a couple of vague memories of days on the ditch, watching neighborhood boys walk the elevated pipe over the sludgy current and then doing it myself to prove I wasn’t scared.

The reason Cady Ditch occupies such a place in my memory is not boys or frogs, but the day my dad told me that a woman had hung herself from a tree in between the Grace Street and Liable Street bridges. Grace Street is where I crossed the ditch on the way to my friend Dalene’s grandparents’ house, and Liable Street took me to softball practice at Shepard Park. It was about 100 feet from the Grace Street bridge that she did it, they said, and I became obsessed for a little while with how small a distance 100 feet was. It didn’t matter that I hadn’t actually witnessed her body there—I could see it just as clearly in my mind’s eye, where I paused on the bridge, straddling my bike, and gazed through foliage to see her silently swinging in the breeze. How far, exactly, was 100 feet, and if she had walked straight out of her back door to the ditch, I wondered, which house had been hers? What did she look like when they finally cut her down? Had I crossed the bridge while she hung there, or while she stared out her back window contemplating the length of rope that waited in a coil in the garage?

Thinking about Cady Ditch, I’m struck again by the tendency of waterways to wear their grooves into both our memories and our landscapes with equal effect. Cady Ditch, built for flood prevention, runs still between the Cady Marsh and the Hart Ditch. In my memory, its path marks the ebbing and flowing freedoms and fears of adolescence: the humanly-constructed contingencies against disaster, widening circles of permission, the growing awareness of death. The spring fed depths of Pleasant Lake mirror the deep place the lake occupies in my sense of self, and both are every age they have ever been and will be, even while they occupy a particular place in space and time. Even the contours of the irrigation ditch at Zandstra’s farm, where we built mud slides through the onion fields that would shoot us out into the shallow canal, remain in my memory, though they’ve been backfilled by strip malls and condos now. I can still feel my body sliding over the mucky knobs of the onions as surely as I can feel my mind sliding over these stories, some massaging my aches and some bruising already tender places.

I look out my window now, as I often do, at the stretch of the Portage River that we can see from our apartment. I’ve watched this river rise and fall for seven years now. I’ve walked its depths and shallows upstream to the Hoffman Pond, past the house that Karen’s family lost to foreclosure and between high banks so unfamiliar from my perspective inside the river that I couldn’t even identify the streetscape I was passing through, though I was less than a mile from home. Our friendship is young yet, but I suspect it will be long, growing more intimate over time until the wrinkles on my body are like the tattoos on a map turtle, tracing out every waterway that has shaped me—every waterway that has calmed, disturbed, intrigued, caressed, and etched me in the endless rocking motion of give and take. From dust we came and, eventually, in some as yet unknown fashion, to dust we shall return. But let me be a speck of sand observing the human drama from the bottom of Cady Ditch. If there is eternal life indeed, let me be silt in a Portage oxbow or muck on the quiet end of Pleasant Lake or clay in a field where children play among the onions, silent in their swelling skins.