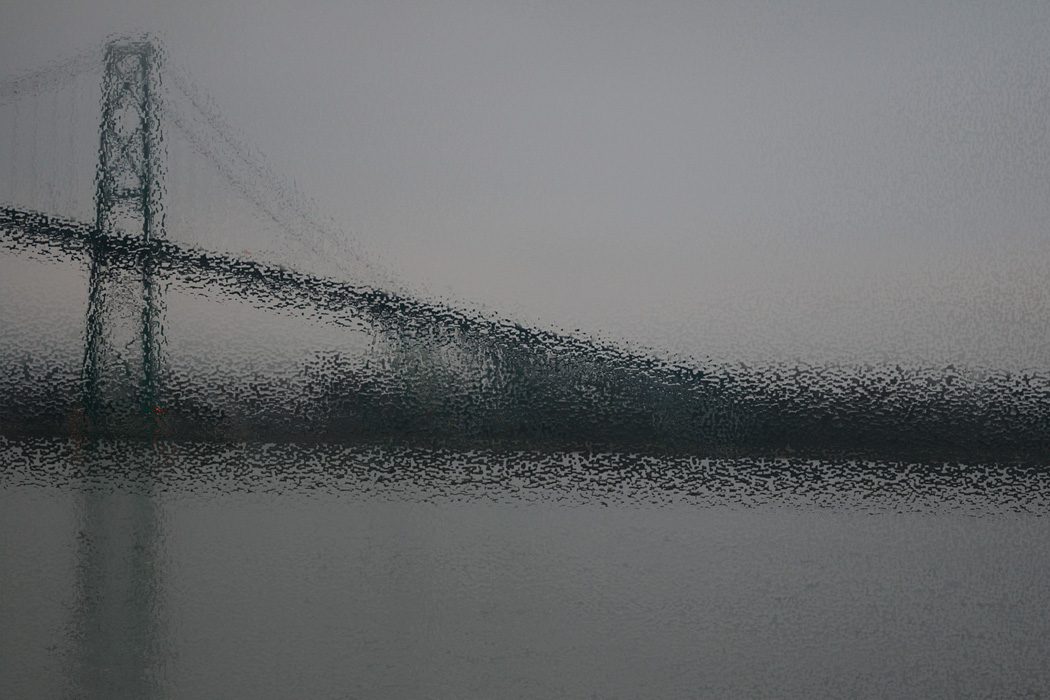

Tacoma, Washington, 2010

On November 7, 1940, a dog named Tubby died when the Tacoma Narrows bridge collapsed into the Puget Sound. An attempt to rescue the cocker spaniel was made but the dog was terrified; he didn’t want to leave the car he knew, and so he bit one of the attempted rescuers, one of whom was the owner of the car. Despite the tons of concrete and heavy cable, a relatively mild wind of forty miles per hour was enough to break the bridge apart. Tubby went down into the water still inside the car. He likely died on impact. His body was never found.

I live in a land of sloughs, marshes, rivers, and inlets that connect the mountains to the sea. Bridges hang in the wet air, connecting Canadians and Americans, mountain people and marshlanders. On sunny days their metal braces glimmer. The painted bridges gleam red and blue. In the rain, particularly the West Coast’s winter storms, bridges loom in the thick air, and despite my love of ferries, bridges – no matter how dark, wet, or icy – are so much easier than having to take a boat to get from Washington to Oregon. Connection is good. When it is working it seems so very easy, and yet what makes all bridges work is the stuff most of us never see, nor make any attempt to understand: math, complex environmental knowledge, an understanding of velocity and aerodynamics, the physics of resonance.

Bridges, no matter of what kind, only work if those that build them know more than the rest of us, and only if those builders understand the connections between all salient factors. It isn’t enough to understand how strong concrete can be. You must also understand its relationship to wind and movement. To hand over our bridge building to someone who understands only the concrete is to invite a future full of remorse for all the Tubbys that will perish as a result. Or, perhaps even worse, it invites a future where we will be the ones that go down with the bridge. As afraid as the future can make me, I’d really rather that didn’t happen, and especially if I fell because I was afraid to leave behind what I thought was safe.